Tarsoly

by Þorfinna gráfeldr

Based on a

find from Jämtland

© Melanie Fischer, November 2013

© Melanie Fischer, November 2013

WHAT I HAVE MADE AND WHY

I have

chosen to reproduce a Tarsoly (pronounced Tar-shoy), a type of decorated belt pouch,

particularly the one that was found at Jämtland, Sweden.

I

decided to make this Tarsoly for several reasons. Firstly, to see if I could;

and secondly, because I believe that adding the accessories, the small bits, to

an outfit is part of what brings it to the next level and helps to turn it from

a costume into real clothing.

…And because I hang out with a lot of “14th century nerds” (their terminology) and need some bling of my own to compete ;)

…And because I hang out with a lot of “14th century nerds” (their terminology) and need some bling of my own to compete ;)

I have been

inspired by a particular individual on Deviant Art who goes by the name

VendalRus. I have admired many parts of his kit, but especially the highly

decorated accessories he wears and particularly his pouches. In further

searches I came across many reproductions of Tarsoly pouches online and found

again and again that the reproductions of the type found at Jämtland to be the

one that appealed to me the most. However, as the reproductions and/or the

castings themselves were all well outside my current financial budget, I had

resigned myself to admiring them online, with the thought in the back of my

head that perhaps one day I would try casting the pieces myself.

Then

one day a friend posted a picture online of a pewter token he had cast using

Bondo as the mould. Intrigued, I decided to try making a Bondo mould myself,

and in the course of trying to come up with something to cast, I remembered the

Tarsoly and thought I’d try to recreate the pouch fittings.

Map showing where

the Tarsoly I am reproducing was found.

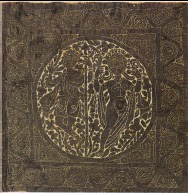

Below is a picture of the Jämtland Tarsoly I decided to try to reproduce:

BACKGROUND

The

Tarsoly was part of a Magyar warrior’s kit and was worn suspended from the

right side of the warrior’s belt to hold fire-starting elements, food, or other

small items. Many recovered Tarsoly were found in the graves of military men

and may have originally had connotations of rank amongst Magyar warriors. It is

possible that Rus traders and soldiers brought the Tarsoly, along with many other

items of Eastern influence, back to Scandinavia from their travels to and from

the Byzantine Empire and surrounding regions via the many trade routes

established in the 8th-11th centuries.

Most of the Tarsoly pouches recovered from graves are of the

type with a solid metal front plate. Only a handful of the type with individual

mounts on the front face of the pouch, such as on the Jámtland pouch, have been

found. These mounts were usually cast in brass, or occasionally silver. They

were likely cast either using the lost wax casting method, or the direct matrix

method, both of which had been in use during the Viking Age.

Map showing the major

Varangian trade routes: the Volga trade route (in red) and the trade route from the

Varangians to the Greeks (in purple). Other trade routes of the 8th-11th

centuries shown in orange.

MATERIALS

USED IN CREATING THE TARSOLY

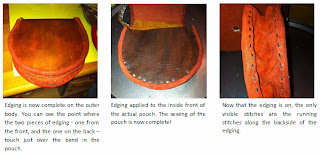

The

pouch is constructed of cow leather for the main body and pig skin for the

pouch middle and edging. It was sewn with black, waxed linen thread. The mounts

are made from pewter.

Due

to my current financial budget, I was limited in the creation of my project to

the supplies I already had on hand. Therefore, certain concessions had to be

made in the construction of the Tarsoly:

As

cow leather would have been readily available, and as I had some on hand, I

decided to use a small piece of vegetable tanned cow hide to form the main body

of the pouch. This leather was however too thick to use as edging. I had a few

pieces of chromium tanned leather, but most of it was also too thick or of a

colour that did not appeal to me. I was left with two choices, a natural deer

skin, or a reddish-coloured suede pig skin. I considered the deer skin but I

had ear marked it for another project, so in the end I opted for the pig skin

as it is known that the Norse kept pigs so pig skin would have been available.

Unfortunately

the pig skin was not large enough for me to cut the edging and the pouch middle

all in one piece, so I instead had to do them in four separate pieces, which

resulted in a lot more stitching than would have otherwise been required. Similarly,

I did not have a piece of vegetable tanned cow hide that was long enough to

make the belt loop and strap, so I had to construct it of two pieces and join

them together to get the full length I needed.

It is believed that the inside of the Tarsoly may have been lined with linen due to the remains of some linen fibres found with the pouch (although, frustratingly, I can no longer find where I read that to document it!) I chose a piece of rust coloured linen to back the front flap because it complimented the colour of the pig skin and the brown dye I planned to use for the pouch, but I did not have enough of it to line the entire inside of the pouch, only enough for the front flap, so there is a raw edge at the top of the flap that could end up fraying if I’m not careful with the pouch.

It is believed that the inside of the Tarsoly may have been lined with linen due to the remains of some linen fibres found with the pouch (although, frustratingly, I can no longer find where I read that to document it!) I chose a piece of rust coloured linen to back the front flap because it complimented the colour of the pig skin and the brown dye I planned to use for the pouch, but I did not have enough of it to line the entire inside of the pouch, only enough for the front flap, so there is a raw edge at the top of the flap that could end up fraying if I’m not careful with the pouch.

I

had some black, waxed linen thread left over from a previous leather working

project, and decided to use it to stitch the pouch together, though I have read

that it is suggested that white linen thread would be more suitable for period

reproductions.

Based on the scale in the picture of the

extant pieces, the pouch appears to have been approximately 12cm x 13cm (plus

strap). It was difficult to get exact measurements of each mount from this

picture, and as I wanted to make sure that all the pieces would be the correct

scale in relation to each other, I decided to use the measurements I found on a

commercial website, Armour and Castings, that does reconstructions of

this particular pouch.

I took the pictures of each individual mount and drew them to the size described in the listing, and printed them out to give me a template to use with the Sculpey when making the Masters.

The measurements I used are as follows:

Centre Plate: 48mm x 45mm

Edge Mount: 20mm x 17mm

Flap Mount: 28mm x 28mm

Strap Mount: 12mm x 16mm

Strap End: 40mm x 12mm

Large Bear Mount: 20mm x 17mm

Small Bear Mount: They did not have the smaller animal head mount (that I am calling a Small Bear Mount) so I had to guess and do my best to make it proportional to the Large Bear Mount.

I used Fiebing’s brand alcohol based Mahogony leather dye to

dye the cow skin.

I used Bondo to create the moulds and I cast the mounts in

pewter.

THE PROCESS OF

CREATING THE POUCH MOUNTS

MAKING THE MOULDS

MAKING THE MOULDS

First I created

masters from Sculpey, a modern polymer clay that you can bake in your oven. It

is fairly easy to work with and can be sanded or carved further after

hardening. You can even add pieces to a baked piece and re-bake it, allowing

you to build up layers in stages rather than all at once.

I used plastic Tupperware-like

containers as the container for my moulds. I created my moulds using Bondo.

Bondo is a polyester resin that hardens when mixed with a catalyst that causes

an endothermic reaction. While Bondo is not a period medium, the

technique used to create the moulds and cast the items from them do not differ

all that much from period methods. The Bondo takes the place of

the clay that an original object or wax copy would be pressed into.

To make the moulds,

I mixed up just enough Bondo and hardener for one half of the mould and poured

it into the plastic container. Before placing my Sculpey master into the Bondo,

I sprayed it with WD-40, a spray lubricant, to act as a mould release (no mould

release is required between the Bondo and the plastic container.) It is

important not to over-spray your masters or the excess liquid can create

bubbles and cause a subsequent loss of detail in the mould. It is also

important to be sure that your entire master is sufficiently covered with the

mould release or it can stick in the mould and it it-self may break, or the

mould may break, when trying to remove it.

Once the master was

coated with WD-40, I pressed it into the Bondo, taking care not to push it so

deep that the Bondo could seep over the top edges of the master. The Bondo was

left to cure between 10 and 30 minutes, depending on the amount of hardener

added to the Bondo (more hardener = faster curing time.)

After the first

half of the mould cured, I created a cone-like shape out of plasticine and

pressed this from the top edge of the mould down so the tip would just touch

the top of the master, making sure to press the edges down so there were no

spaces, or ‘undercuts’, between the bottom half of the mould and the

plasticine. This cone of plasticine creates the channel or ‘sprue’ needed to

pour the molten metal in when casting. Once the plasticine sprue was in place,

I sprayed the entire surface of the first half of the mould, including the

plasticine and the back of the master, with the WD-40, ensuring that everything

was covered. If there is no detail on the back side of your master, you can be

more liberal with your use of WD-40 at this stage, as there is no detail to

lose.

The second half of

the mould was again left to cure for approximately 10 minutes, to the point

where it had hardened, but still not fully cured. At this stage, the Bondo is

still hot so you need to be careful. Using an exacto-style knife, I sliced off

a thin layer of the Bondo along all the edges of the mould where the two halves

overlapped. I have found it is slightly easier to do this before the Bondo is

fully cured, but it can also be done once the Bondo has fully cured and is

cool. This removes any places where the Bondo from the top half of the mould

may have seeped down around the edges along the bottom half of the mould. By

cutting away this overlap, we reveal the line between the two halves of the

mould and can insert the edge of the knife into the line and carefully work it

around all the edges and separate the two halves of the mould.

Lastly, I removed

the master from the mould and checked for any problems in the detail such as

air bubbles or holes that could be quickly repaired by adding a dab of bondo to

fill them in. At this point, any areas that required additional clean-up were

sanded and/or carved until the desired result was reached, and all holes for

the mounting posts were drilled into the backsides of each mould. As the second

half of the mould always picks up a faint outline of the master, it is easy to

place the mounting posts and drill them in appropriate places.

I chose to drill

the posts rather than make them out of Sculpey because it is infinitely easier

to make perfectly straight posts with a drill than it is with a thin piece of

Sculpey that will need to be reinforced with a pin of some sort to give it

structural strength before baking. To allow air to escape when pouring the

molten pewter into the mould it is important to add tiny air holes to the

posts. I did this using a pin drill and a tiny drill bit. It is important that

the air holes are as small as possible so that your molten pewter does not flow

all the way out your air hole to the back of the mould where it can trap the

casting in the mould.

CASTING THE MOUNTS

I used a cast iron

pot to melt my pewter in, placing it on a burner on my stove at about ‘8’ until

it had melted and then reduced the heat to about ‘5’. It is absolutely

imperative that you make sure that no water can come into contact with your

molten pewter, as it can cause a steam explosion (as the water evaporates) and

send molten pewter flying in all directions. Protective clothing, glasses, and

gloves are recommended.

Unlike soapstone

moulds, holding the Bondo mould by hand while pouring generally does not create

enough of a seal between the two halves of the mould. Using spring clamps to

hold the mould together solves this problem and also makes it easier to hold

onto the mould, which can get very hot. Usually I used between 2 and 4 clamps,

depending on the number of masters ganged together on each mould. This helps

create a tight seal between the two halves to minimize excess pewter around the

edges of the cast item, called ‘flash’.

A bit of talcum

powder dusted over the mould aids in the flow and release of the pewter. I

dusted my moulds every three or four pours.

Once the mould was

powdered and clamped together, I took a small amount of pewter in my ladle,

just a little bit more than was necessary to fill the mould, and poured it into

the sprue in one smooth pour until it filled. It is important to pour it all at

once as the force of the pewter pouring from above is what helps push the

molten pewter deeper into the mould.

The pewter was then left to cool until it had ‘set’. You can tell when the pewter has set by looking at the pewter in the top of the sprue. If it has dulled from the chrome-like shininess of its molten state to a slightly more grey, less shiny colour and is solid, it has cooled enough to be removed from the mould. If not, it needs more time. With practice, it becomes easy to recognize when your pewter has cooled enough to be removed.

The pewter was then left to cool until it had ‘set’. You can tell when the pewter has set by looking at the pewter in the top of the sprue. If it has dulled from the chrome-like shininess of its molten state to a slightly more grey, less shiny colour and is solid, it has cooled enough to be removed from the mould. If not, it needs more time. With practice, it becomes easy to recognize when your pewter has cooled enough to be removed.

Once the pewter had cooled

enough, I removed the clamps from the mould and separated the two halves. Using

a knife, I fit it under the main body of the casting and pried it gently straight

upwards to pull the posts out of the mould without breaking them or bending the

main body of the casting. I then snapped or snipped off the sprue and returned

it to the pewter pot, and left the casting to cool completely before final

cleanup.

If there was any flashing

or other areas that needed to be removed from the cast item, I would snip and

file them using small jeweler’s files until they were cleaned up and ready for

mounting.

WHAT

I LEARNED FROM THIS PROJECT

From a hands-on perspective of

actually making the Tarsoly

About Bondo Moulds:

While Bondo is great for

making a quick mould for a limited run, there are disadvantages to using it as

well:

A Bondo mould does not

produce an end result as fine as what can be achieved using a soapstone mould.

Fine detail is often lost or bubbled when air gets trapped under the master. I

have been experimenting with ways to combat this, and have had some success by

brushing on a thin layer of the Bondo to the face of the master directly, and

then placing that into the rest of the Bondo mixture to avoid catching air

between the face of the master and the mixture.

The Bondo holds the heat a

lot longer than the soapstone. Subsequently it takes longer for the pewter to

set in the mould, and thus longer between each pour. I tested a Bondo mould

against a soapstone mould and found I was able to do approx. 3 pours in the

soapstone mould for every 1 pour into the Bondo mould, a significant difference

in time. This has led me to the conclusion that if there are going to be a

large number of the item cast, it may be worth the effort to carve the mould in

soapstone.

The Bondo mould also

reacts to the heat more and develops more flex the hotter it gets, absolutely

necessitating the use of clamps in order to hold the two halves of the mould

together tightly enough to get a decent seal. Even using the clamps, the Bondo

moulds also seem to result in a lot more ‘flashing’ on each cast, resulting in

a lot more clean up required after each pour. This also lends weight to the

conclusion of using a soapstone mould for items that require multiple castings,

as cleaning up each casting can take considerable time.

About Attaching Mounts:

Much to my consternation,

I discovered that, even when you think you have your mounts lined up exactly

where you want them to go, and you press the posts on the back of the mounts

into the leather to make marks to punch with your awl, somehow the mounts can

still end up not quite straight or sometimes even downright crooked. This

happened with the mounts on the strap, where a few of them are a bit angled and

so don’t sit perfectly in line with the rest of them. Fortunately it is only a

minor difference and not glaringly obvious when looking at it. The ‘clasp’

section on the inside front of the pouch on the other had is considerably

crooked and the part that disappointed me most of all with the entire project.

One edge had already become rounded due to a second too long on the belt

sander, and somehow, even after carefully lining it up, that same side ended up

lower than the other, emphasising it even more. I considered moving it, or

making a new one, but did not for two reasons. The first being, I did not want

visible holes left in the front of the pouch that would result if I moved the

clasp; the second being that the amount of cleanup required to make that piece

useable was quite a lot, and considering that I already didn’t want to move the

clasp to avoid the extra holes, it did not seem worth the effort to replace the

existing one in the same position. So, since it is not visible when the pouch

is closed, which is how the majority of people are going to see it, it is more

of an unfortunate annoyance to me than an overall flaw.

WHAT I WOULD DO DIFFERENTLY NEXT TIME

Sculpey,

the material I used to create my masters, is deceptive. What seems perfectly thin

and light enough in Sculpey often results in a pewter casting that is thicker

than desired. If I were going to try making another Tarsoly from scratch, again

using Sculpey for the masters and Bondo for the moulds, I would make sure to

make the masters much thinner than I did this time around. I think that most of

the mounts could stand to be almost half as thick as they are. That being said,

at some point I think I would someday like to go back to carving the masters in

soapstone, as it is a period method and makes it easier to cast multiples.

For

the sewing of the pouch, I would endeavor to do the edging and pouch middle out

of one piece of leather to cut down on the amount of stitching that was

required. Using separate pieces for the edging meant I had to go over the same

section twice as many times as I would have had to with only one piece. I would

also prefer to use leather that would more likely have been used in period over

the suede I used this time.

I

would also use a larger piece of linen so that it would line the entire inside

of the pouch and cover all the folded over mounting posts from all the mounts.

This would not only be more aesthetically pleasing, it would prevent fraying of

the open edge of linen, and provide a layer of protection between the mounting

posts that stick through the leather and whatever you may put in the pouch; to

avoid scratches from the posts, and to avoid catching the posts when you put

something in or take something out of the pouch.

It

would also be nice to be able to source or create some period dye or oils to

use on the leather instead of the Fiebing’s brand commercial dye I used.

LIST

OF SOURCES

http://vendelrus.deviantart.com/

www.armourandcastings.com

Graslund, Anne-Sofie "Beutel und Taschen" Birka

II:1: Systematische Analysen der Graeberfunde ed. Greta

Arwidsson

Carlson ,

I. Marc Leatherworking of the Middle

Ages © March 3, 2013; Web;

Accessed: November 2013; http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/leather/leather.pdf

Söderberg , Anders

“Scandinavian Iron Age an Early Medieval Ceramic Moulds – Lost Wax or

Not or Both?” Exarc, ©2012; ISSN: 2212-8956; Publishing date: September 15, 2012; Web; Accessed:

November 2013; http://journal.exarc.net/issue-2012-3/ea/scandinavian-iron-age-and-early-medieval-ceramic-moulds-lost-wax-or-not-or-both

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Varangian_routes.png

http://www.hurstwic.org/index.html

http://www.regia.org/leatwork.htm